In Pennsylvania and across the country, Black Americans experience health disparities. Health disparities are disproportionate health conditions and inequalities that exist among all ages in a certain population, including chronic conditions, access to care, preventive screenings, and mental health.

But health disparities are preventable, and UPMC is committed to creating health education and programming that combats these issues. Our goal is to partner with community members and train health care providers to ensure that everyone has access to healthier lifestyles.

The first step to preventing health disparities starts with identifying and understanding them. Health disparities can result among Black patients from multiple factors, including but not limited to:

- Individual and behavioral factors

- Inadequate access to health care

- Educational inequalities

- Environmental threats

- Poverty

Read below to learn more about health disparities and what UPMC is doing to ensure equity in health care.

-

Heart Disease and Black Americans: What’s The Connection?

Heart disease is the No. 1 cause of death for all Americans. But did you know that Black Americans are more likely to suffer heart failure and even more likely for heart failure to happen earlier in their lives?Read More

-

Dr. Steven Evans Addresses Racial Health Disparities

Dr. Steven Evans, MD, is an advocate for the elimination of cancer disparities among Black American women.Read More

-

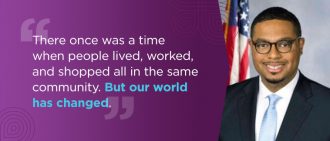

Health Disparities Q&A With Representative Austin Davis

Austin A. Davis was the first Black person outside the city of Pittsburgh to win an elected state office in southwestern Pennsylvania.Read More

-

Health Disparities Q&A With Dr. Simhan

Hyagriv Simhan, MD, MS, is executive vice chair of obstetrical services at UPMC Magee-Womens Hospital and director of clinical innovation for UPMC women’s health services.Read More

-

Health Disparities Q&A With Dr. Conti

Tracey Conti, MD, is executive vice chair of the Department of Family Medicine at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, and an advocate for the elimination of health disparities.Read More

-

Health Disparities Q&A With Dr. Essien

Utibe Essien, MD, MPH, is a physician-researcher who focuses on racial/ethnic health disparities in cardiovascular disease care and social determinants of health, such as food insecurity and housing instability.Read More

-

UPMC HealthBeat Podcast: Connecting the Community to Important Health Screenings

Lyn Robertson, DrPH, MSN, BSN, discusses efforts underway to connect uninsured and underinsured people with free cancer screenings.Read More

-

How Does COVID-19 Affect Racial and Ethnic Minorities?

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), members of some racial and ethnic minority groups are more at risk of severe illness or death during public health crises.Read More

-

Quiz: Test Your Knowledge of Cancer Health Disparities

Health disparities can impact a person’s cancer diagnosis and treatment. Some Americans are more likely than others to have certain kinds of cancer, less likely to get cancer screenings, and more likely to die from the disease.Start Quiz

-

Breast Cancer in Black Women: Disparities in Cancer

For the first time, Black women have been added to the list of groups considered “high risk” for breast cancer, according to the American College of Radiology.Read More

-

Black Maternal Mental Health: The Challenges Facing Black Mothers

Pregnancy and childbirth can be an exciting time for mothers, but it also can be a difficult one. Black mothers may face even more challenges.Read More

-

Diabetic Retinopathy: A Leading Cause of Blindness

Black and Hispanic people have an increased risk of developing the condition.Read More

-

Why the COVID-19 Vaccine Is So Important for Minority Communities

Tracey Conti, MD, executive vice chair of the Department of Family Medicine at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, discusses the impact of health disparities on minority communities and what that means for COVID-19 vaccination efforts.Read More

-

Understanding COVID-19 Vaccine Health Disparities

Many Black Americans and underserved communities continue to face health disparities. These disparities can affect their access to the COVID-19 vaccine. Vaccination is critical to stop the spread of COVID-19 and prevent the occurrence of severe illness and death.Read More

-

Kidney Transplant and Health Disparities

Black Americans are three times more likely to need a kidney transplant than other populations, mainly due to health disparities.Read More

-

Black Maternal Mental Health: The Challenges Facing Black Mothers

While Black Maternal Health Week is important in recognizing Black mothers everywhere and the challenges they face, we believe year-round efforts are needed to ensure that these issues and inequalities are adequately addressed.Read More

-

Health Disparities Q&A With Dr. Bledsoe

Demond E. Bledsoe, PhD, LPC, is a senior program director with UPMC Western Psychiatric Hospital, where he provides clinical support to inpatient behavioral health units in UPMC hospitals and select outpatient facilities across Pennsylvania. His research and scholarly writings focus on the impact of psychological trauma as well as diversity in behavioral health and clinician training. Dr. Bledsoe has worked in a variety of treatment settings and has served on numerous state and local boards andRead More

-

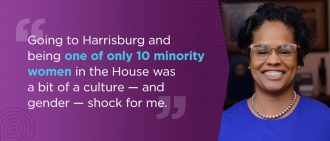

Health Disparities Q&A with Representative Morgan Cephas Pennsylvania House of Representatives

Morgan Cephas represents the 192nd legislative district in West Philadelphia, the community in which she was born and raised. Now in her third term, Rep. Cephas sits on the House Appropriations, Health, Insurance, and Labor and Industry committees.Read More